Introducing a New Weekly Serialization of Captain's Dinner

Our first installment features a shipwreck, a desperate situation at sea, and a murder most foul.

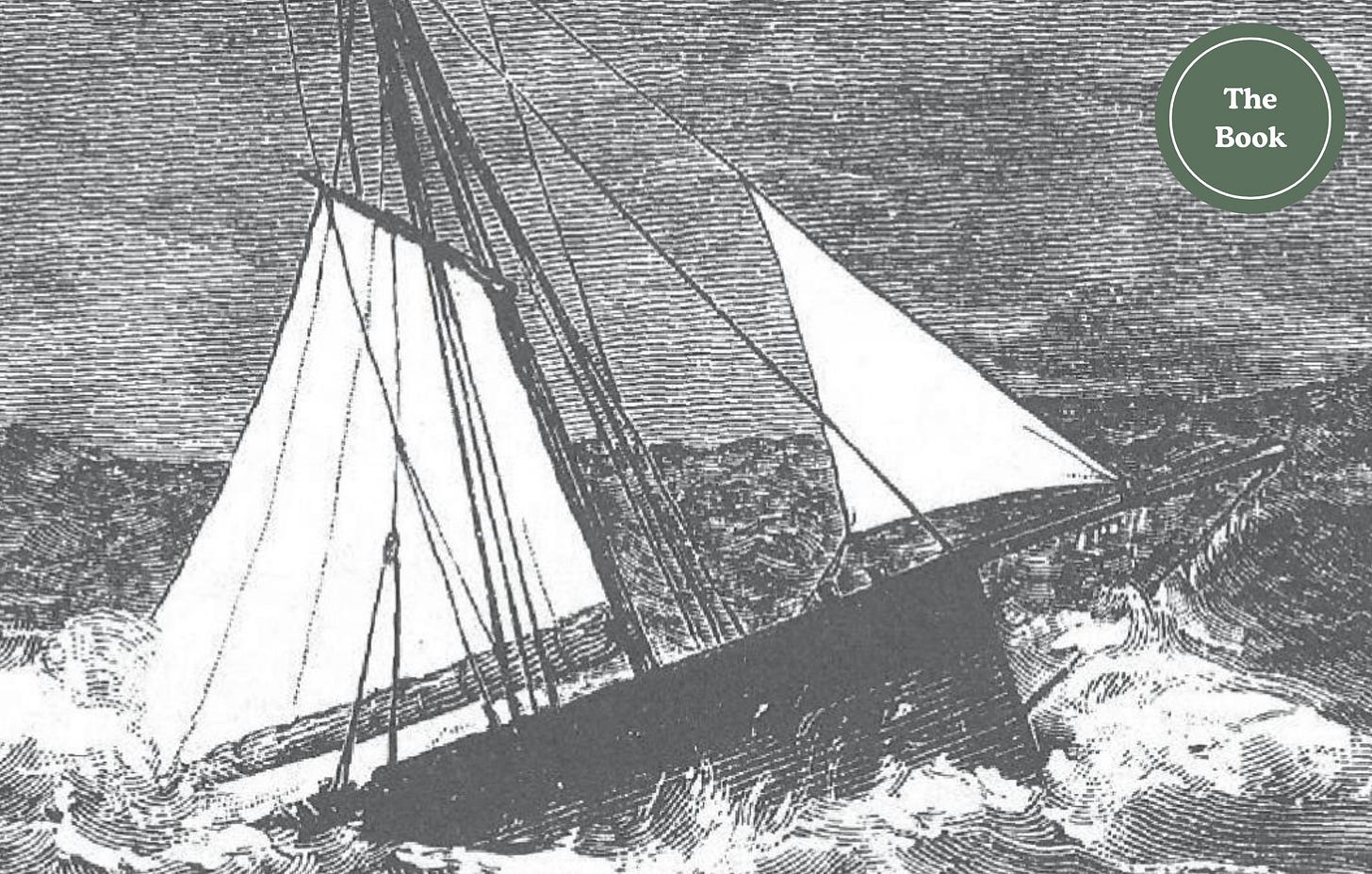

England, 1884. The Age of Sail, a centuries-long period of global exploration dominated by sailing ships, is drawing to a close. Steamships are quickly taking over, supplanting the glorious old-style schooners, clippers, and square-riggers that have long ruled the oceans—and offered employment and adventure to millions of men. But the old ways live on through the wealthy and their yachts, those proudly impractical playthings of rich men. One such rich man, a prominent Australian lawyer named John Henry Want, has purchased the smart-looking yacht Mignonette from an English shipyard, and he’s seeking a captain to sail it across treacherous oceans all the way to Australia. One sailor is foolhardy enough to take the daunting assignment—and soon, he’ll live to regret it…

When Captain Thomas Dudley was hired to transport the yacht Mignonette across the world, his friends and associates urged him not to make the voyage. Dudley was an experienced yachtsman, but he had never crossed the equator, a notable marker of the most well-traveled sailors, much less sailed as far as Australia. And he had certainly never done either in a mere yacht, meaning he had no firsthand knowledge of the risks that lay ahead, nor how to prepare for them.

But Dudley ignored the naysayers and assembled a crew of three: able seaman Edmund Brooks, navigator Edwin Stephens, and cabin boy Richard Parker. All four men came to the voyage with their own hopes, challenges, and concerns—and in the tough labor market facing sailors amid the dying Age of Sail, all four needed the paycheck. Dudley, a family man with an offer to take over an aunt’s sailing supply shop in Sydney, wanted to see Australia firsthand before deciding to uproot his wife and children. Brooks, warned by his friends that the long journey was too much for the Mignonette, was ultimately persuaded by a generous salary. Stephens, an experienced sailor still struggling to find work six years after his involvement in a disastrous shipwreck, ignored his misgivings for want of employment. And as for young Richard Parker, a seventeen-year-old orphan eager for his first real sea voyage, he “intended to make a man of himself,” recalled his adoptive mother, who begged him not to go.

On May 19, 1884, the Mignonette set sail. The tide was high and the winds were favorable, with a light breeze out of the southeast. By June 2, as the Mignonette sailed away from Madeira, an island off the coast of Africa, the blue skies and smooth sailing seemed a rebuke to the doomsayers back home. “The Mignonette proved a capital sea boat,” Brooks remembered. Spirits were high, he said, and “we were comfortable together on board.”

As the Mignonette continued south, trouble began a few days after crossing the equator, when the Mignonette got caught in a heavy cross sea. In a cross sea, waves collide at right angles, creating a grid-like pattern that can be perilous for ships sailing through it. Patterson’s Illustrated Nautical Encyclopedia describes a cross sea as “a confused, ugly sea, very dangerous for low-sided vessels.” Cross seas toss ships from side to side, driving them off course—and sometimes cause them to sink.

As the Mignonette rocked violently in the churning waters, the crew knew that the ship was now in danger, and they scrambled to respond. They took down the topmast to lessen the wind’s impact on the small boat. The rough weather continued in fits and starts. By June 25, the wind had shifted and was blowing from the northwest. Dudley reduced the sails further, hoping the winds would calm. The northwest wind continued until June 30, when a fierce wind blew to the south-southwest. Then, as suddenly as the bellowing winds had appeared, they stopped. On July 2, the weather was calm, the breezes were light, and the Mignonette was sailing smoothly again.

But it was not long before the next storm came. On July 5, the Mignonette was about 1,600 miles northwest of the Cape of Good Hope when conditions once again turned treacherous. “The wind,” Dudley later said, was “blowing a fresh gale.” He recalled it being “thick with rain.”

With danger looming, Dudley decided to heave to, or hold the boat in place, until conditions improved, a common technique for protecting ships in rough seas. In heaving to, the sails and the rudder are made to essentially cancel each other out, so the boat almost stands still. Dudley told Stephens to take the helm while he helped Brooks and Parker to reef (or reduce the area of) the squaresail. Then, Dudley used a small axe and some tacks to nail canvas over the skylight, while Brooks and Parker lashed the lifeboat to the deck.

Moments after Dudley drove the last tack into the skylight cover, a massive wave swelled up from the ocean. It towered halfway up the Mignonette’s masthead, and as soon as they saw it, the men knew they were in trouble. Stephens shouted, “Look out!” Dudley glanced up from under the boom “only to see,” he later recalled, “a big sea coming right down on the top of us.” He was stunned by the wave’s sheer size. “I shall never forget it as long as I live,” he said.

“I shall never forget it as long as I live.”

The force of the ocean was overwhelming. Brooks later said that he could not understand how they weren’t swept overboard. They had managed to cling to the deck, but they could see instantly that the Mignonette had suffered crippling damage. The wave’s brutal force had torn away the bulwarks, the planking meant to keep the waves from breaking over the deck, and laid the starboard side completely open. Struggling to recover his footing, Stephens saw the sea come rushing in through the mangled planks. “My God, her side is knocked in!” he shouted. “She is sinking!”

The men looked on in horror as the Mignonette filled with seawater. The yacht had suffered a wound no ship could survive. It was going to sink, there was no question, and unless they acted quickly, they would go down with it.

For the next five minutes, there was “nothing but confusion,” Stephens later recalled. The men were desperate to escape in the lifeboat, but they had just lashed it down tightly to keep it from washing overboard. While Stephens fought to steer the foundering yacht, the other three men surrounded the dinghy and struggled to get it loose. Dudley was still holding the small axe he had been using to hammer tacks. He used the blade to hack at the cords holding down the stern of the lifeboat, then passed it to Brooks, who cut the cords on the bow. While the Mignonette continued to fill with water, the men lowered the dinghy into the sea.

Because there were no provisions in the lifeboat, the men raced to grab whatever supplies they could. Dudley yelled to Parker to bring up a breaker (or cask) of freshwater from below. Parker went down and returned with a breaker, which he threw into the water near the dinghy. The wooden cask would float, and Dudley would be able to pull it from the ocean once he boarded the lifeboat.

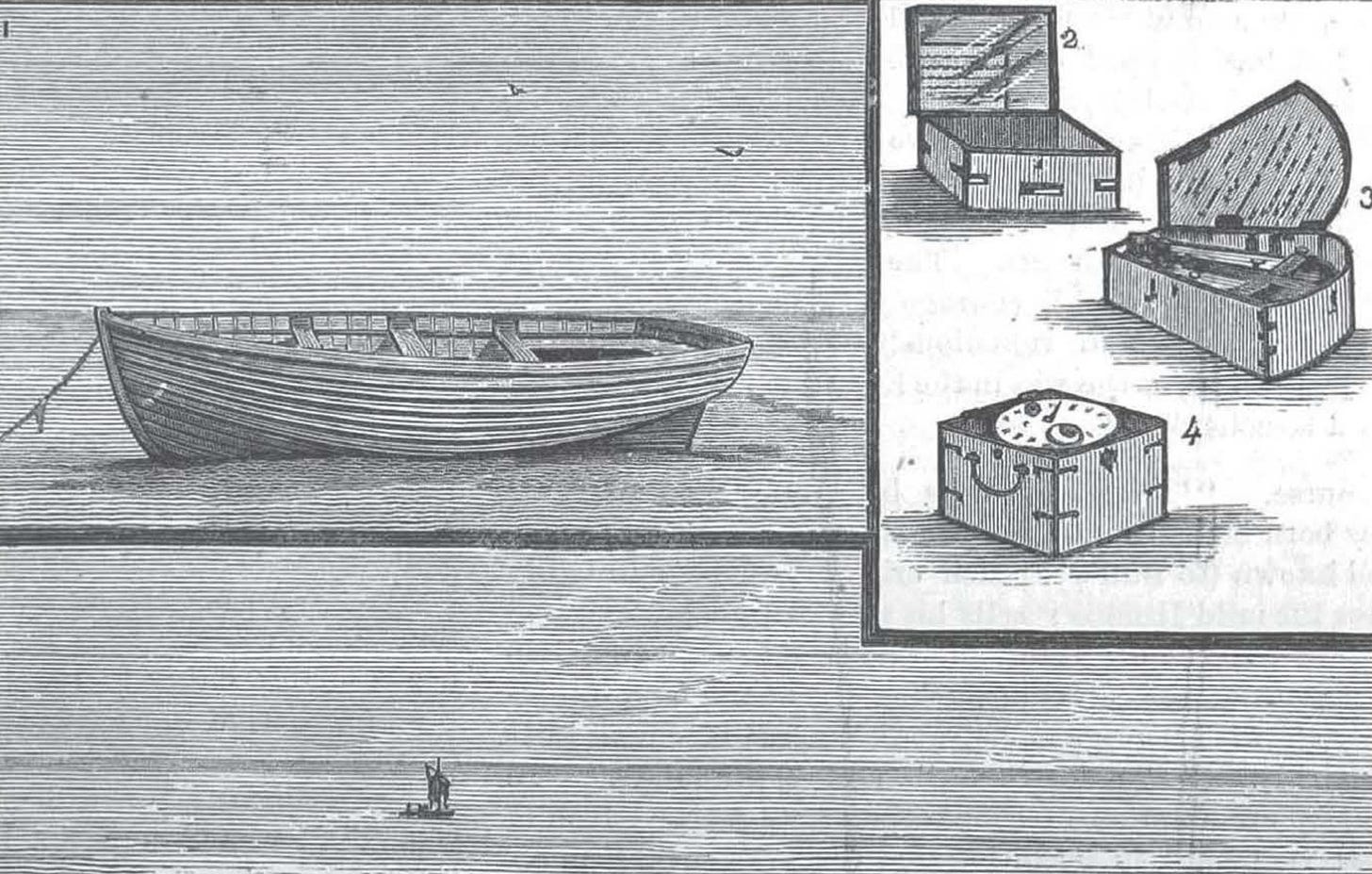

Before abandoning ship, Dudley went on his own retrieval mission. He rushed into the cabin, which was now filled waist-deep with water. Dudley was looking for food and drinkable water, and the sextant to navigate by the sky once they were afloat in the lifeboat. He had trouble finding anything, with the water rising and gear floating loose in the cabin. Finally, he found the sextant and the chronometer, and he pried off the binnacle, the cylindrical container that held the ship’s compass. He grabbed six tins of food—preserved meat, he thought.

Water was pouring into the Mignonette. Stephens, Brooks, and Parker were yelling from the lifeboat as Dudley came up on deck. He tossed the compass into the lifeboat and threw the sextant and chronometer into the water nearby, mindful not to damage the floor planks of the lifeboat by throwing the heavy gear right in. He tried to toss the food tins into the dinghy, but only one made it. With the Mignonette sinking fast, Dudley finally dropped into the lifeboat. The men hustled to pull their crucial supplies out of the water. They grabbed the sextant and the chronometer, bobbing nearby in their wooden cases, and they managed to retrieve one more of the food tins. The other four were lost in the roiling ocean. They found the wooden stand that went with the breaker of water Parker had thrown from the yacht, but they could not find the cask itself. They searched for the precious drinking water, but they never found it.

The men had escaped the sinking Mignonette with little time to spare. Dudley used the lifeboat’s oars to row away from the yacht as it sank into the water before their eyes. “Down she went,” Dudley later said, “not five minutes from the time the sea struck her.”

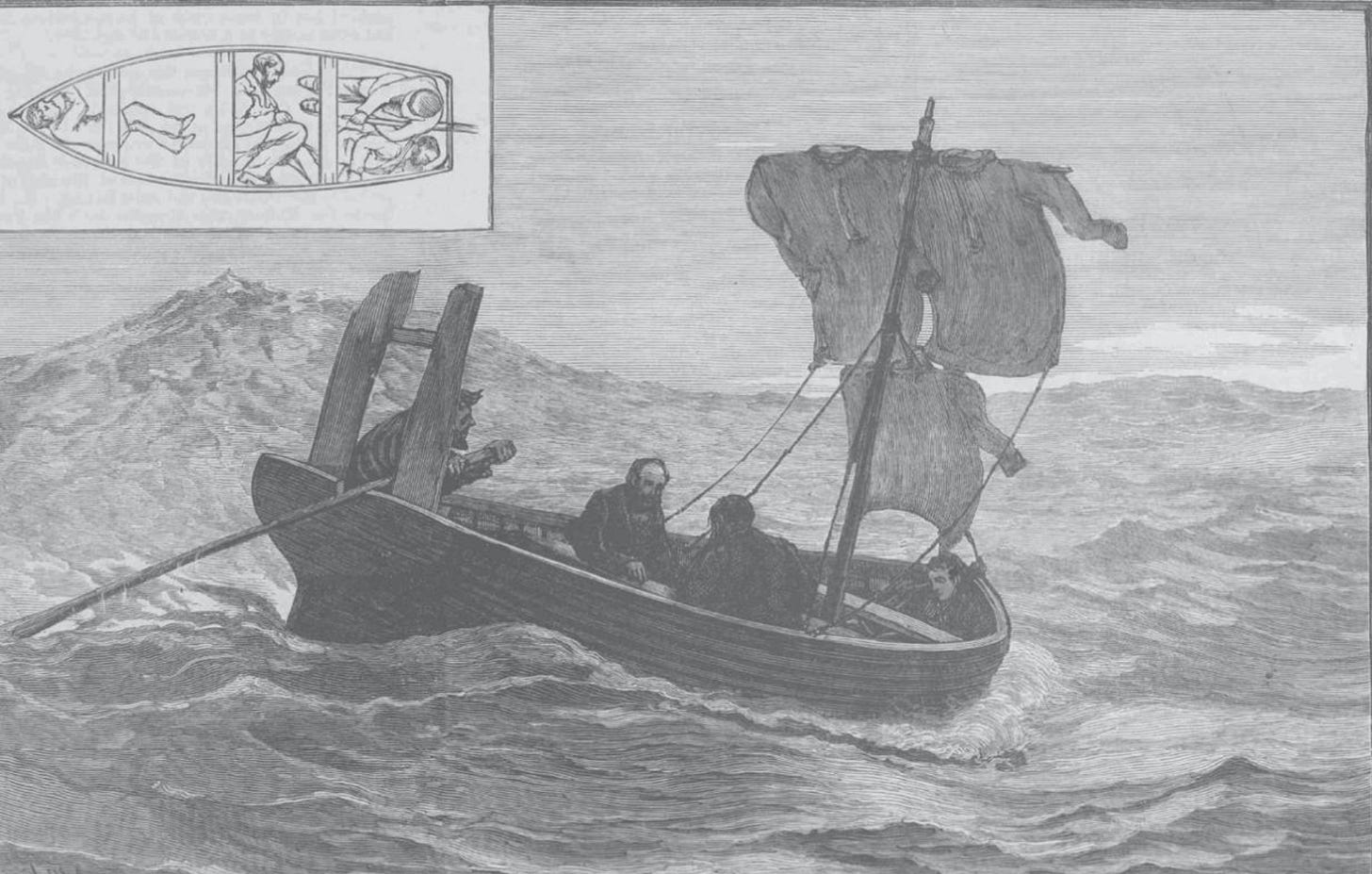

The men had not been pulled down with the Mignonette, but their ordeal was just beginning. Dudley, Stephens, Brooks, and Parker were crowded into a thirteen-foot-long dinghy that was roughly four feet at its widest. Its sides were only twenty inches high, against the tumbling waves of the ocean, and its thin planks, which were just a quarter-inch thick, seemed terribly fragile. It was strong enough to hold the men afloat, but it was designed for light rowing over short distances, not to stand up against an ocean that had already torn through the far larger and sturdier Mignonette.

Fragile and drenched as it was, the lifeboat was all the men had, and their first challenge was to make sure that it could survive in the middle of the South Atlantic. They decided to make a sea anchor, which could be used as a brake and might help in steering the boat. They did not have much to work with, but they cobbled one together from the compass binnacle, the wooden stand from the lost water cask, and some extra boards from the bottom of the lifeboat. Since the dinghy had no rudder, and they did not have the materials to construct one, they would have to steer with just the dinghy’s oars and their improvised sea anchor.

Even if they managed to steer in a direction where they hoped to find a passing ship or an eventual landfall, there was no telling how long that might take, so another crucial problem was their lack of shelter from the elements. The dinghy had no cabin, of course, and no sail to serve as a roof or awning. The men had only their own sodden clothing between themselves and the blistering sun of day, the bracing cold of night, and the occasional driving rain.

But the greatest threat of all was the lack of food and drinkable water. The only food in the lifeboat was in the two one-pound tins Dudley had retrieved from the Mignonette—and the men soon got some bad news about them. Dudley had thought the tins contained meat, but when Brooks inspected them, he recognized them as turnip tins. As for drinkable water, their best hope would be to collect rainwater, though without any receptacles, the best they could do was hold their oilskin coats toward the sky. As they’d soon discover, the coats only captured “about a wineglass full,” Brooks later recalled.

The men had only their own sodden clothing between themselves and the blistering sun of day, the bracing cold of night, and the occasional driving rain.

The castaways did not know exactly where they were, but they understood that their location was an unfortunate one. The Mignonette had sunk in the South Atlantic Ocean at about 27° 10′ south latitude and 9° 50′ west longitude—and that happened to be one of the most remote places on earth. They were almost equidistant between Africa and South America. The Cape of Good Hope was some 1,700 miles to the southeast, and Rio de Janeiro was more than 2,000 miles to the southwest. The prevailing winds in the area would not be helpful. They blew from the southeast, which meant the lifeboat would drift toward South America, the farther of the two continents, and away from the nearest islands. Even if the men rowed steadily, their prospects of reaching land in any direction were daunting.

Given their location, a passing ship would be their more likely hope for rescue, but even that was highly unlikely. They were adrift in an enormous expanse of ocean where there was little ship traffic, and the winds were pushing them into ever more desolate waters. And even if a ship passed, it was by no means certain the men would be spotted. The crew of a passing ship would not be actively scanning the water looking for lifeboats the way a rescue mission would, and they easily might miss a tiny dinghy bobbing along on the waves.

The men made it through that first night, and the next, and the one after that. With each passing night, it became clearer that despite the severe deprivations of food and freshwater, and the dangers that loomed from every direction, it was actually possible for the four of them to survive in the small, fragile dinghy. Somehow the men, for the most part, remained stubbornly hopeful. Stephens regularly told the others they were sure to be rescued by a boat soon. Brooks later recalled that hearing this from Stephens, an experienced navigator, gave them confidence they would eventually be saved. Brooks would later say he himself probably “had the best spirits” of all the men. Parker, who was the least knowledgeable about life at sea, was also convinced they would all survive. He kept telling the others they would soon spot land. Only Dudley, the captain, was becoming gloomy. He believed they would soon die, but he also thought they had to keep trying to survive and trust in God.

On July 10, the fifth day after the Mignonette sank, Brooks spotted something in the distance. Whatever it was, it appeared to be moving. Brooks was eventually able to make out that it was a sea turtle, and he steered the dinghy around toward it. When the lifeboat drew close, Stephens was able to grab the sea turtle by the flippers and turn it over. Brooks let go of the oar he was using to steer and helped lift the turtle into the boat.

The capture of the sea turtle was a remarkable windfall. Apart from rainwater, sea turtle blood is one of the best sources of life-sustaining liquids available at sea. Fish blood is too rich with protein and salt to ward off dehydration, but sea turtle blood has a different chemistry, making it a highly effective substitute for freshwater. Although the men were focused on their thirst, the sea turtle would also provide pounds of meat. After five days of near starvation, the men’s relief and eagerness were overwhelming. The first thing they did was start drinking the sea turtle’s blood, which they found enormously refreshing after days of parched mouths. Once their thirst was quenched, they ate the sea turtle’s flesh. (Brooks would later speak highly of the taste.)

But the relief didn’t last. The men planned to save some of the blood for later, but when they scrambled to catch it in the chronometer box, seawater sprayed in. “We lost the biggest part of the blood through the salt water,” Brooks later recalled ruefully. Before long, the castaways resorted to something even more desperate than drinking turtle blood. Around the eighth day in the lifeboat, they began to drink their own urine. Then, on the eleventh day, the food from the sea turtle ran out. The men were back to being constantly hungry and thirsty. The grueling conditions were causing them to develop body sores; meanwhile, their legs were swollen to the knees and turning black.

On July 16 or 17, while Brooks was steering and Stephens was lying down, Dudley made an announcement. It was necessary, he told the others, to kill one of the men in the lifeboat and eat him so the other three could survive. “We shall have to draw lots, my boys,” he said.

Dudley was invoking a tradition known as “the custom of the sea.” It had long been accepted in the sailing world that when there was not enough food or water to keep everyone alive, lots could be drawn to decide who should be killed and eaten. It was something to be done only in the most extreme circumstances, and Dudley had decided that they had reached that horrible point.

The fact that the sailing world embraced the custom of the sea did not mean all the men in the lifeboat had to—and they did not. When Dudley suggested that it was time to draw lots, Stephens and Brooks did not agree. “I and Mr. Stephens would not hear of it,” Brooks recalled. As for Parker, Dudley did not solicit his opinion on drawing lots. In Dudley’s eyes, Parker’s status as cabin boy apparently put him so far below the full crew members that his views should not be taken into account. It was an unjust act of disenfranchisement, because if there was a drawing, Parker would be a participant whether he wanted to be or not—and he might end up as food and drink for the other three.

Days later, Parker made a confession. He told the others he was secretly drinking seawater at night while they were sleeping. He admitted that he had drunk a bailer full of seawater, which was about a quart, and then another half bailerful. Now he had become ill as a result. He had diarrhea, and he was in pain. He had taken to lying down on the bottom of the boat, trying to sleep. Parker now appeared to be the weakest of the four, while Stephens seemed to be the next sickest, with internal pains and legs so swollen he could hardly move.

When Parker became sick, Dudley repeated his call for drawing lots. Brooks and Stephens again rejected the idea.“Let us all die together,” Brooks said. “I should not like anyone to kill me, and I should not like to kill anyone else.”

It seemed to Dudley that things were about as bad as they could be. On July 21, in a dark state of mind, he added to the letter he had begun scribbling to his wife on the back of the chronometer certificate the day after the Mignonette went down. “We have been here 17 days; have no food,” he wrote. “We are all four living, hoping to get a passing ship. If not, dear, we must soon die.”

On July 23, the situation in the lifeboat was worse than ever. The men had not eaten in eight days, except for the sea turtle skin they had chewed on when the meat was gone. It was the longest they had gone without food. More critically, they had not had freshwater in five days. They caught some rainwater the next day, but the situation remained desperate. There were still no passing ships and no signs of land. The only chance for relief within their control was the gruesome one that Dudley proposed. They could decide to kill one of the men in the lifeboat and drink his blood, or they could keep waiting.

Dudley finally gave up on drawing lots and proposed a new plan. At about three o’clock in the morning, the captain spoke to Stephens. Brooks was steering, and Parker was still lying at the bottom of the boat. They could not hear the captain and the first mate talking. In making his appeal to Stephens, Dudley tried to persuade him that this would not be much of a murder at all. Parker was going to die anyway, and quite soon, he insisted.

“We are all four living, hoping to get a passing ship. If not, dear, we must soon die.”

Dudley’s new plan also addressed another concern Stephens may have had. The captain had not been able to get Stephens to agree to a drawing in which he himself would have a one in four chance of being selected to be killed and eaten. But now, he was offering a plan in which Dudley, Stephens, and Brooks would all be safe. Dudley was stipulating from the start that Parker would be the one to die. The captain’s proposal was a major departure from the custom of the sea, and it lacked some of the classic virtues of that maritime tradition. It did not have the inherent equality of the custom of the sea, which required that everyone on the boat have the same chance of living or dying.

Even with the promise that he would personally be safe, Stephens still hesitated. “If there is no vessel in sight by tomorrow morning, I think we had better kill the lad,” Dudley said. Stephens responded that they should “see what daylight brings forth.”

When morning broke on July 25, once it was clear that the arrival of daylight had not changed anything, Stephens told Dudley that he believed Parker should be killed. Dudley and his mate now had an agreement, a conspiracy of two. They finalized their plan outside the earshot of Brooks, who would not have agreed, and Parker, who had no idea what lay in store.

Dudley began by moving Brooks away from Parker. It was not easily done, since the lifeboat was only thirteen feet long and the cabin boy was lying in the middle of it. “You had better go forward and have a sleep,” the captain advised Brooks. The able seaman moved to the front of the dinghy and lay down in the bow of the boat. Dudley remained further aft while Stephens steered. Stephens nodded at Parker and then at Brooks. Brooks later said this was the moment he realized what was about to happen, and he tried to block it out. “I had my oilskin coat over my head, trying to sleep,” he later recalled. He covered his eyes before he could see any more.

“Hold his feet,” Dudley told Stephens. Stephens stood ready to hold Parker down if it was necessary, and he watched as Dudley moved toward the cabin boy. Dudley took out a white-handled penknife. Before he used it, he offered up a prayer for forgiveness so that “our souls might be saved.” The cabin boy lay before him in the bottom of the boat, with his arm over his face. Dudley knelt down next to him.

“Now, Dick, your time has come,” Dudley said.

“What, me, Sir?” Parker murmured in response.

It was clear from Parker’s words that he knew what was about to happen. Dudley did not strike from behind, ending Parker’s life before he could appreciate what was going on. He allowed the cabin boy an awful moment of knowledge of what was about to occur.

“Yes, my boy,” Dudley replied.

Dudley aimed the blade at the side of the neck that Parker’s arm was not covering and plunged it in. Parker remained still, even as the blood spurted out. The cabin boy’s end came quickly. “In a minute all was over,” Stephens said. Dudley remembered it as taking just fifteen seconds.

Brooks was three feet away when Dudley stabbed the cabin boy. He heard “a little noise” through his oilskin coat, he recalled. When Brooks lifted the coat from his head, he could see Parker had been stabbed to death. Brooks fainted away for a minute or two and woke to see Dudley and Stephens drinking Parker’s blood. One drank from the bailer, the other from a turnip tin.

Brooks had not wanted Parker killed, but now that he was dead, the able seaman hoped for some of the blood. “Give me a drop,” Brooks asked Dudley. The captain shared what he had, but there was not much drinkable liquid left. Brooks said the blood he received was “quite congealed,” but he “sucked it down” as well as he could.

Dudley and Stephens stripped Parker’s body, throwing his clothing overboard. When they were done, they sliced open the corpse and removed the internal organs. Dudley, Stephens, and Brooks devoured Parker’s heart and liver while they were still warm. Then they tore flesh from Parker’s body and immediately began eating it.

The men dug into their meal enthusiastically. It did not deter them that the meat and blood were human—or, more particularly, that it came from a shipmate and friend. Brooks later said that they fully enjoyed the food and drink that had suddenly appeared before them. “I can say that we partook of it with quite as much relish as ordinary food,” he said.

It was the most they had eaten since the sinking of the Mignonette nearly three weeks earlier. Parker’s flesh and blood reenergized the other three. They all agreed that they were “different men” as a result of it.

If the men gave any thought to whether they might get in trouble for what they had just done, they would have quickly rejected the possibility. Even though they had not drawn lots, the killing of Parker had saved three lives, as they saw it. No Englishman had ever been prosecuted for cannibalism at sea, and they had no reason to believe they would be the first.

Adapted from CAPTAIN’S DINNER, by Adam Cohen, published by Authors Equity. Copyright © 2025 by Adam Cohen.